The Visual Resonances of

Frances Barth

447 Space

April 25 through June 6, 2025

Exhibition Review by Raphy Sarkissian

The expansive fields of color within these distinctly engaging and wittily orchestrated paintings of Frances Barth are frequently negotiated with such iconographic signs as a segment of a bricked wall, a Saarinen Tulip table, a pyramidal form, or a television set. At other times the abstracted figures that appear within unadorned monochromatic spaces hint at the sculptural languages of such forerunners of abstraction as Jean Arp or Barbara Hepworth. Fragments of architectonic forms are also represented frequently, articulating pictorial space as a simultaneity of autonomy and iconography. In this manner, Barth punctuates the self-containment of abstraction through signs that represent objects within our material world and cultural reality.

Dating from 1970 through 2025, the twenty paintings on view at 447 Space testify to an artistic practice that is singular and handsomely incorporates a series of theoretical and aesthetic concerns of the past fifty-five years. As Karen Wilkin notes in her insightful essay of the exhibition catalogue, this highly selective survey “can be considered as a kind of staccato, miniature retrospective,” inviting us to “think of the ineffable nuance of Giorgio Morandi’s still life, here translated into warmer, more varied chromatic terms.” (1)

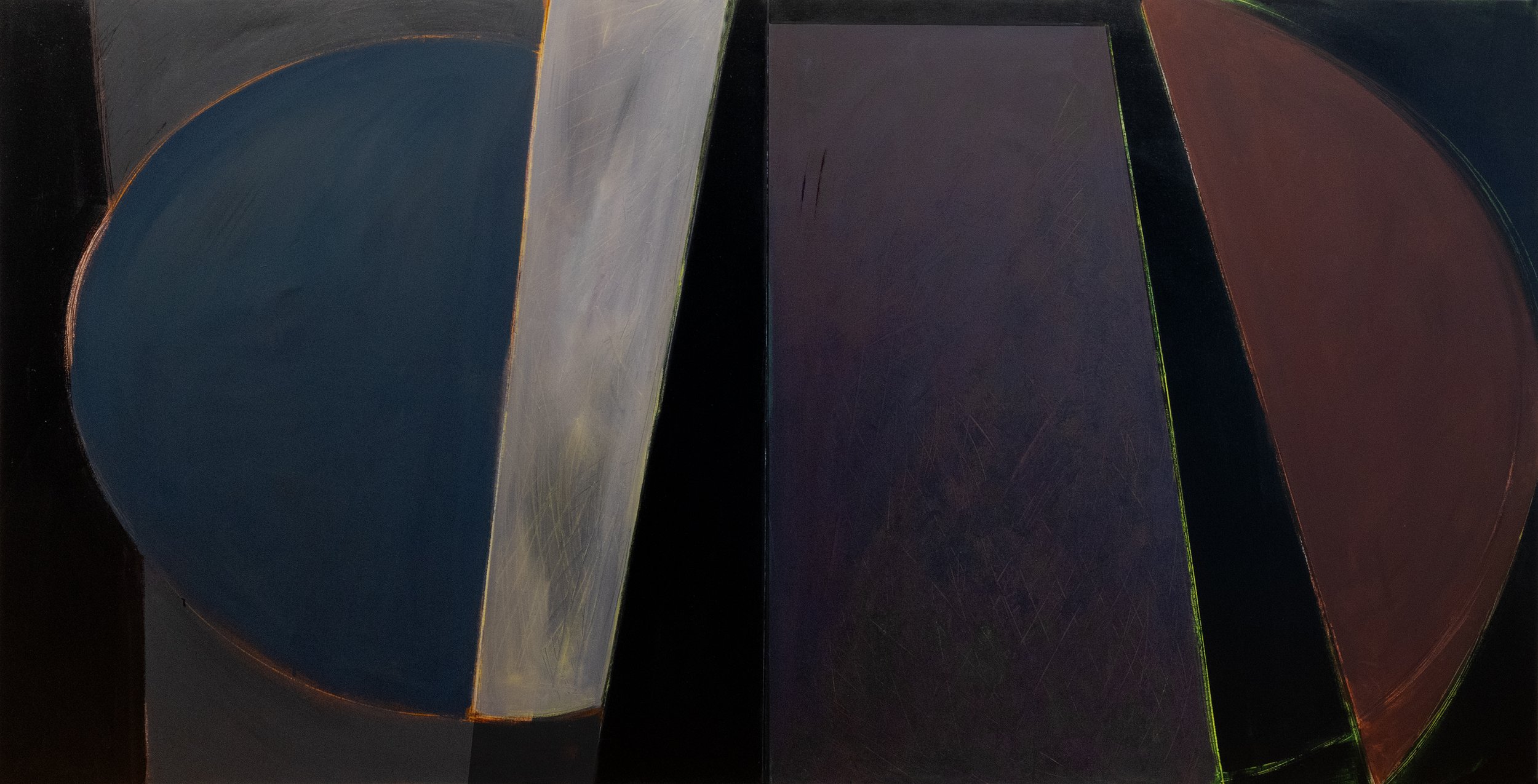

Mariner (1977), a striking diptych that is six feet high and twelve feet wide, comes across as a dusky and austere cosmos of geometric shapes rendered in a forceful and notably painterly manner. Expressive brushstrokes articulate trapezoidal forms that are partly integrated with spherical figures within the two pictorial registers. Evoking such references that range from the oculus and vision to celestial bodies and rays of light, this painting of Barth arrests the beholder through its considerable scale, luminous contours, chromatic resonance, calculated design, and gestural rendition.

Frances Barth, Mariner, 1977. Oil on canvas, diptych, 72 by 144 inches. © Frances Barth. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

Whereas Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art directs our perception toward far-off galaxies, Barth’s Mariner may conjure up the orderly, complex and chaotic nature of the cosmos, along with the fundamental forces that play a crucial role in shaping the universe and governing interactions at all scales, from the smallest particles to the largest structures: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force. And by shifting our interpretation of Mariner from cosmological associations to psychoanalytic ones, the painting recalls the ideas of Jacques Lacan in the Four Fundamental Principles of Psychoanalysis: “Light may travel in a straight line, but it is refracted, diffused, it floods, it fills—the eye is a sort of bowl.” (2) The enigmatic spherical and trapezoidal figures in Mariner come forth as abstractions of the circular and rectangular mosaic patterns upon the floor in Hans Holbein the Younger’s Ambassadors (1533) of the National Gallery in London.

Gazing at Mariner, we are also reminded of the intriguing allure of Jasper Johns’ painting titled Diver (1962-63) of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Indeed, in the late seventies Barth was manifestly forging an aesthetic vocabulary that entailed at once an integration of and departure from elements of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptualism—as partially embodied in the dramatic yet subdued atmosphere of Mariner.

Frances Barth, Emo, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 96 by 52 inches. © Frances Barth. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

Emo (1997) tidily conveys a sense of a window overlooking an imaginary architectonic landscape in the lower part of the composition. This volumetric figuration is set off by the depiction of a brickwork pattern through three rows of rectangular shapes on the painting’s upper section. In ylo, brk (2000), the visitor encounters an analogous composition, where the formalist devices of pattern, order, arbitrariness, protrusion, and recession give way to a contemplative composition. Whereas the viewer can effortlessly associate the title ylo, brk to the words “yellow” and “brick” that are correlated to the perspectivally articulated brick pattern, Emo as a title remains puzzling until Barth explains: “I worked on my boarded-up house trying to do almost everything myself for twelve years. The mortar at the back of the building had washed out, and the older man who came to help me taught me to mortar brick and I worked with him—his name was Emo.” (3) In this sense, Emo calls to mind the interconnections of the art object, tools, and labor, recalling the thought of the Austrian philosopher Ernst Fischer: the “first toolmaker, when he gave new form to a stone so that it might serve man, was the first artist.” (4) Emo hence reveals the possibility of painting to refer as much to itself as it does to what is beyond itself through its title—to the artist’s life and surrounding social reality.

Frances Barth, ylo, brk, 2000. Acrylic on canvas, 96 by 52 inches. © Frances Barth. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

Though executed over three decades after Barth’s formally innovative and thought-provoking painting Untitled Blue (1973), currently in the Whitney Museum’s collection, Views (2005) retains to some measure the geometric sensibility and sparseness of the former. Along with a modified configuration that has become primarily distributed, Barth has augmented the painting’s uncluttered space with softly rendered undulations and painterly curves on the right, suggesting a dialogue between the Earth’s crust and the troposphere, between land and sky. Establishing such interactions between land (material and corporeal) and sky (atmospheric and ocular), Views lends itself as a model of our tactile and optical faculties.

In Views, meticulous painterly marks and compositional elements combine to form a pictorial space that seems to be on the verge of acquiring symbolic or iconic weight. The vertical lines of the elegantly abstracted “window” in the lower left corner function as perspectival echoes of the slender band anchored to the right edge of the canvas, suggesting depth and variable points of view across the visual field and pictorial space. As though testing abstract painting’s capacity to maintain its autonomy in addition to serving as a referential device, Views incites wide-ranging allusions not only to the history of abstraction but also to paintings of the Old Masters and early modernists. In the lower left corner of the painting, shutter-like forms set within an illusory fenestration or a rectangular aperture eloquently remind us of the backlit windows in such works as The Cestello Annunciation (1489) of Botticelli; A Scholar Near a Window (1631) or Philosopher in Meditation (1632) of Rembrandt; and Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (circa 1657-59) of Vermeer.

Frances Barth, Views, 2005. Acrylic on canvas, 52 by 96 inches. © Frances Barth. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

Despite its high degree of abstraction, it is revealing to think of Views of Barth also in relation to such paintings as Woman at the Window (1822) of Caspar David Friedrich; The Artist’s Sister at a Window (1869) of Berthe Morisot; The Blue Room (1901) of Picasso; and The Studio (Vase before a Window) (1939) of Braque. And while Mondrian’s synthesis of Impressionist and Fauvist elements to depict windows in a Little House in Sunlight (1909-early 1910) is in stark contrast to Views, this painting of Barth is somewhat inseparable from Mondrian’s forthcoming and pioneering geometric language.

Regarding the vastness of bare spaces within her paintings, Barth has characterized them through the concept of “slow time,” as we read in her catalogue essay “Time Travel: One Thing Leads to Another.” Here Barth notes, “The interaction of this shifting space, color, and scale, as well as the large horizontal format in some of the paintings, made the paintings have a ‘slow time,’ a breathing presence.” (5) This notion of “slow time,” recalling one of the fundamental methods of Agnes Martin’s creative process, is inimitably encapsulated within Views.

Installation view of Frances Barth: A Painting Conversation / 55 Years. © Frances Barth. Photo by Michellé Hoban. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

The visual grammar of Barth takes on yet another compelling turn within Venice (2015), a horizontally formatted work composed of four wood panels. Here the viewer confronts aspects of two antithetical exemplars of painting: Barnett Newman’s highly abstract “zip” paintings that bear reconsidered notions of sublimity and Eric Fischl’s psychologically charged figurative paintings that carry a sense of film noir. Though Venice is devoid of the depiction of humans, the ghostlike signs of a Saarinen Tulip table and television set placed within primarily monochromatic rectangular spaces suspend Barth’s aesthetic between the sense of vastness of the color fields within Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950-51) of the Museum of Modern Art and the psychologically charged drama within Fischl’s Slumber Party (1983) of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Frances Barth, Venice, 2015. Acrylic on four wood panels, 24 by 116 inches. © Frances Barth. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

When asked to comment on the theme of the television set in Venice Barth responds, “I was thinking how many people don’t look around them or nature anymore—so I thought it was funny to see the mountains in the TV.” (6) Through its spread-out monochromatic format and restrained color scheme, Venice imparts a sense of both materiality and limitlessness, only to interject it with the hyperreality of visual imagery generated by electrical signals and cathode ray tubes. As if having interlocked notions of sublimity and ordinariness that circulate within the mediums of painting and television, Venice may prompt the onlooker to interrogate the mythical and metaphysical aspects of mankind, heroism and sublimity—three concepts embedded in Newman’s Latin title.

Installation view of Frances Barth: A Painting Conversation / 55 Years. © Frances Barth. Photo by David Riley. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

In his influential 1940 essay “Towards a Newer Laocöon,” Clement Greenberg described modernist painting’s formalist direction by writing: “The picture plane itself grows shallower and shallower, flattening out and pressing together the fictive planes of depth until they meet as one upon the real and material plane which is the actual surface of the canvas.” (7) While these emblematic paintings of Barth carry that sense of flatness and planarity, they concurrently bring to mind the ambivalent and critically charged thoughts of Andy Warhol when he said, “I always suspected that I was watching TV instead of living life.” (8)

Installation view of Frances Barth: A Painting Conversation / 55 Years. © Frances Barth. Photo by David Riley. Courtesy of the artist and 447 Space.

Devised in the same vein as Venice, the multipanel paintings of Barth titled Stacking (2019), Travel Triptych (2019), and push (2022) interconnect the nonobjective and iconographic. For Barth modernist abstraction and figurative representation need to coexist, as they are equally indispensable from painting’s inherent nature, vision, our perceptive realm, motion, movement, and reality. The paintings on view in this revelatory exhibition lend themselves to be akin to the pioneering dance theories of Yvonne Rainer and Joan Jonas, whose performances are marked by task-oriented action and rejection of spectacle. Having performed in the groundbreaking choreographic works of Rainer and Jonas from the late sixties to the mid-seventies, Barth redirects such elements of dance as body, action, space, time, gesture, and energy onto the pictorial surface and into the pictorial space—deftly, conceptually, and with formal reserve.

Notes

1. Karen Wilkin, “Frances Barth: Five Decades,” in Frances Barth: A Painting Conversation / 55 Years, exhibition catalogue (New York: 447 Space, 2025), pp. 3-5.

2. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York and London: Norton, 1981), p. 94.

3. Frances Barth, interview by author, New York, NY, May 18, 2025.

4. Ernst Fisher, in Berel Lang and Forrest Williams, Marxism and Art (New York: Longman Publishing, 1972). Cited in Laurie Schneider Adams, The Methodologies of Art (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1996), p. 61.

5. Barth, “Time Travel: One Thing Leads to Another,” in Frances Barth: A Painting Conversation / 55 Years, pp. 7-10, here p. 9.

6. Barth, interview by author, New York, NY, May 18, 2025.

7. Clement Greenberg, “Towards a Newer Laocöon,” in Perceptions and Judgments, 1939-1944, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), pp. 23-41; here p. 45.

8. Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), p. 91.